01 March 2000 --

This is a two-part series.

Part II (02 March 2000)

Ng Min Li

Physiotherapist

Breaking the laws of work can put you at risk of developing musculoskeletal injuries. Read on to find out how you can avoid them.

The word "ergonomics" is derived from the Greek words "ergon" (which means work) and "nomos" (which means laws). So, ergonomics literally means "the laws of work". Ergonomics is concerned with ways of designing work tasks, work tools and work environments to match human capacities and limitations. The goals of ergonomics are:

- to increase safety and comfort of workers;

- to reduce work efforts and work-related injuries;

- to improve the efficiency and productivity.

Ergonomics is multifaceted. It looks into the physical, environmental and psychosocial aspects of work. The table below lists some of the different elements involved.

Since work performance depends a lot on comfort, it is important to consider all ergonomic factors when making improvements in the office. If comfort is ignored, peak performance can drop. Fatigue can set in and may eventually lead to pain or injury. This usually happens slowly over time and is often unnoticed until it is too late.

Risk factors contributing to musculoskeletal injuries

Common basic office activities involve sitting in front of a computer terminal and operating it by typing or moving and clicking a mouse. While these activities may not be hazardous for a worker who does them occasionally, they can set the stage for injuries for those who have no choice but to sit in front of a computer screen and type for long periods every working day. Common injuries that result are:

- tendinitis/tenosynovitis (inflammation of tendons or tendon sheaths due to repetitive tensing of tendons and muscles, e.g. DeQuervain Tenosynovitis)

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (compression of the median nerve that pass through the carpal tunnel at the wrist)

These injuries are commonly referred to as repetitive stress/strain injuries (RSIs) or cumulative trauma disorders (CTDs). Such musculoskeletal injuries rarely originate from one event or a particular factor. Instead, they develop over time from a variety of factors, some of which can be controlled.

Work-related factors that present the greatest risk for musculoskeletal injuries are:

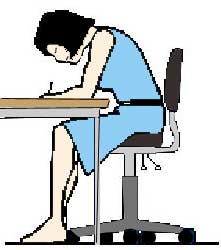

- fixed and constrained posture that are often awkward, uncomfortable and maintained for too long a time

- repetitive and forceful hand/finger movements

Posture. Proper posture minimises stress on muscles and joints. However, even with good posture it is necessary to move or change positions frequently to minimise strain and fatigue and improve blood circulation. Holding the upper body still in an upright position (while sitting at the desk) requires a lot of muscular effort and contributes to a static load. In addition, holding one's head at an optimum distance from the screen and maintaining one's arms in the proper typing position increase the static load on the upper body, especially the neck and shoulders. Poor work posture can further increase this static load, making the body even more susceptible to musculoskeletal injuries. Poor posture can result from:

- non-adjustable workstations and seats

- poor layout of the workstations

By making proper work area adjustments, adopting proper work postures and habits and providing adequate rest and stretch breaks, the risk of injuries can be decreased.

Repetitive Movements. Repetitive movements like typing and operating the mouse pose a dynamic load on our joints and muscles, in addition to the static load encountered while sitting at the desk. These movements when repeated hundreds or thousands of times, hour after hour, day after day and year after year, can cause wear and tear and strain to our tendons and muscles in our forearms, wrists and fingers. Using excessive force when typing adds more load to these structures, accelerating fatigue and degeneration.

Pace of Work. The pace of work determines how much time working muscles have for rest and recovery between activities. The faster the pace, the shorter the recovery times become, increasing the rate of fatigue and thereby the risk for RSIs. Through proper planning and organisation, a person can set his or her work pace, avoiding last minute rushes. However, external factors beyond a person's control can increase the work pace. Such factors include having tight deadlines and being overloaded with work.

References:

- Etienne Grandjean: Fitting the task to the man - a textbook of occupational ergonomics, 4th edition, Taylor and Francis, 1988

- Cumulative Trauma Disorders in the Workplace Bibliography, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 95-119, September 1995

- Officewise - A guide to health and safety in the office, OHS Bk 1, Comcare Australia, 1996

- Office Ergonomics, OSH Answers, Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & sSafety, www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/ergonomics/ergonomics.htm

Date reviewed: 29 February 2000